Poilievre’s Will to Power, Notwithstanding

Poilievre has now rooted the argument for the notwithstanding clause more firmly in right-wing populism. If the Charter becomes a dead letter, the Charter will have been brought down by polarization.

The original aim of this research note was to reflect on the way the author had been approaching the “notwithstanding clause” in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, particularly the uselessness of the attempt to devise a single framework for understanding the increasingly frequent use of the clause by Canadian provincial governments. Thanks to the comments of a discussant at the recent conference of the New England Political Science Association, it became clear that Quebec’s use of the clause is a separate issue from its use on the rest of Canada, and as such needs to be studied separately. In short, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms lacks legitimacy among most of the francophone political class because the 1982 Constitution Act is illegitimate in light of the National Assembly’s unanimous rejection of patriation. Limiting the application of the Charter of Rights to legislation addressing the French language and identity questions reflects the belief that the related constitutional questions ought to be addressed within Quebec itself.

On the other hand, in English-speaking Canada, views of the notwithstanding clause, and the Canadian constitution as a whole, increasingly come through the prism of polarization, and the belief that the 1982 Constitution Act was the work of the Liberal Party of Canada advancing its partisan interests. In 1982, the Progressive Conservative Party voted against patriation in the House of Commons, consistent with decades of the Right’s skepticism toward Liberal proposals to distance Canadian institutions and symbols from Great Britain. (For example, the Progressive Conservatives opposed the adoption of the current Canadian maple leaf flag, preferring to keep the existing design based upon the Red Ensign.) The conservative side of politics held to the Westminster tradition of parliamentary supremacy, rejecting the concept of judicial review of legislation against an entrenched rights charter. As a condition for their support for adding the Charter to the 1982 constitutional package, Western Canadian provinces, led mostly by conservative governments, sought a legislative override of court decisions related to certain sections of the Charter.

The leading body of scholarship detailing conservative objection to the Charter comes from F.L. Morton, political scientist at the University of Calgary and former Alberta cabinet minister, who argued that the Charter of Rights not only took political decisions away from elected legislatures and handed them to unelected courts, but also elevated the concerns of disability rights groups, prisoners’ rights advocates, environmental activists, ethnocultural groups, and LGBTQ activists, groups who viewed “the people” as a “problem.” (He does not mention minority language groups, who play a central role in Charter politics in Quebec.) Morton went well beyond a simple argument for parliamentary supremacy to suggest that the Charter went against the will of the people, or in 2020s terms, is too woke.

It is this populist framework, in which the Charter contradicts the will of a murkily defined people, that drives the current debate over the notwithstanding clause in English-speaking Canada. The conservative governments of Ontario, Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick have all involved the notwithstanding clause since 2019, and have used it on issues that fall broadly under the culture war. Ontario briefly used it to impose a contract upon educational workers, a common populist target, and Saskatchewan and New Brunswick used it to require minors to obtain parental consent when asking their schools to address them by a new (transgender) name or pronoun. In all these cases (as well as for Bills 21 and 96 in Quebec), legislatures invoked the notwithstanding clause preemptively, without any court having ruled against the legislation on Charter grounds. Alberta has passed several pieces of legislation, including the Sovereignty Act and the Provincial Priorities Act, that question the federal division of powers but do not invoke the notwithstanding clause as such.

The notwithstanding clause has to date only been invoked at the provincial level by conservative parties on the grounds that the Charter of Rights is a tool of encroaching federal power under a Liberal government. No federal Conservative government has invoked the Charter, and until the past week, the Conservative Party of Canada avoided taking positions on the Charter of Rights. On April 28, this changed when Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre told the Canadian Police Association that his government viewed the clause as an option to reenact the former Harper government’s legislation restricting bail and parole that the Supreme Court struck down on Charter grounds (recall that Morton lists prisoners as a Charter constituency). While this would not be particularly noteworthy beyond advocating use of the clause at the federal level instead of discouraging the provinces from using it, what was more interesting is Poilievre’s theory of the constitution and popular will, as he explained to the audience:

I will be the democratically elected prime minister — democratically accountable to the people, and they can then make the judgments themselves on whether they think my laws are constitutional, because they will be.

There are several interesting things about Poilievre’s conception of representation. First of all, he is claiming a direct relationship between the prime minister (not even the government or cabinet) and the electorate. The prime minister and cabinet in a parliamentary system emerge organically from the majority faction in a democratically elected parliament, and can be removed at any time by a majority of members. Similarly, he claims direct prime ministerial ownership of laws, apparently separate from any legislature even though the legislature enacts them by majority vote. Finally, “the people” render direct judgment about constitutionality, going around the courts.

Later in the week, Poilievre attacked businesses in an article in the National Post, in which he wrote

Businesses will get nothing from me unless they convince the people first. If you do have a policy proposal, don’t tell me about it. Convince Canadians that it’s good for them. Communicate your policy’s benefits directly. When they start telling me about your ideas on the doorstep in Windsor, St. John’s, Trois-Rivières, and Port Alberni, then I’ll think about enacting it.

We again see the view that the prime minister is the direct voice of “the people,” and that mediating organizations like businesses associations and civil society have no legitimate role in the political process.

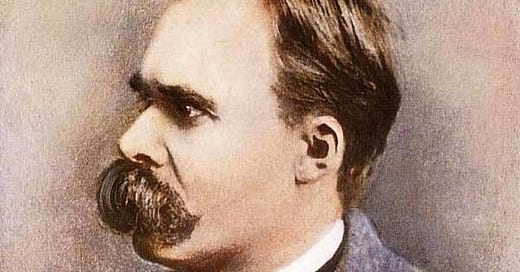

Poilievre is not a fascist, but in this instance he is borrowing the Führerprinzip, the idea that the utterances of the leader constitute the law, and that the leader decides the content of laws personally. The idea itself did not originate with National Socialism, but finds its roots in the writing of the 19th century German political philosopher Friedreich Nietzsche, who rooted the leader principle in what he termed “the will to power.”

Poilievre has now rooted the argument for the notwithstanding clause more firmly in right-wing populism. He is also strengthening the narrative that the Charter of Rights is a Liberal partisan project. If the clause comes to be used so widely by Canadian governments at all levels that the Charter becomes a dead letter, the Charter will have been brought down by polarization.

References:

https://search.worldcat.org/title/5262497

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/hitler_commander_01.shtml

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/poilievre-notwithstanding-clause-1.7188964

https://www.nationalobserver.com/2024/05/07/opinion/pierre-poilievre-coming-your-charter-rights

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/poilievre-charter-rights-notwithstanding-1.7195547

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/historic-potential-notwithstanding-federal-use-1.7193180

https://thehub.ca/2024-05-09/joanna-baron-pierre-poilievre-flirts-with-the-notwithstanding-clause/

https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1718&context=ohlj